latest

Traffic’s Back, But Patterns Have Changed

By Chris Lisinski

The morning slog on Interstate 95 toward Boston from points north and south of the city is six-plus minutes faster today than it was before COVID-19 rewired commuting. A morning rush hour trip on a well-traveled stretch of Interstate 93 southbound now takes nearly four minutes longer than three years ago. And on the Fall River Expressway, traffic flow changes are barely perceptible.

Welcome to the brave new world of driving around Massachusetts, where roadway congestion continues to inflict grating headaches on drivers but the patterns themselves have changed.

More than two years after Gov. Charlie Baker first declared a COVID-19 state of emergency and nine months after he lifted that emergency declaration, state officials are still grappling with volatility across the transportation landscape as both employers and employees have both adopted new patterns and stuck to old ones.

In June, Highway Administrator Jonathan Gulliver declared that “traffic, for all intents and purposes, is back to about 2019 levels.” On Wednesday, a couple of months removed from the worst of the omicron-fueled winter surge that trimmed congestion down, Gulliver said the latest data indicate Bay State roads are again “seeing traffic return pretty quickly.”

What remains difficult, Gulliver said, is extrapolating trends from vehicle volumes clogging up highways, which rebounded far more quickly than public transit after initial lulls but have also fluctuated with the peaks and valleys of the public health crisis.

“This is still something we’re continuing to watch closely,” Gulliver told the Department of Transportation’s board on Wednesday. “It seems that we were just getting back to this point when delta ended before the next surge hit us, so we don’t really have a great handle on where things are going yet.”

As has been the case for much of the pandemic, granular route-by-route traffic patterns have shifted from previous norms even as the overall volume approaches its past levels.

Gulliver presented data reflecting the change in travel times for the morning and evening peaks headed in both directions on more than a dozen of the most heavily traveled highways around the greater Boston area. Most show slightly to significantly faster travel, while traffic has surpassed pre-COVID levels on some routes.

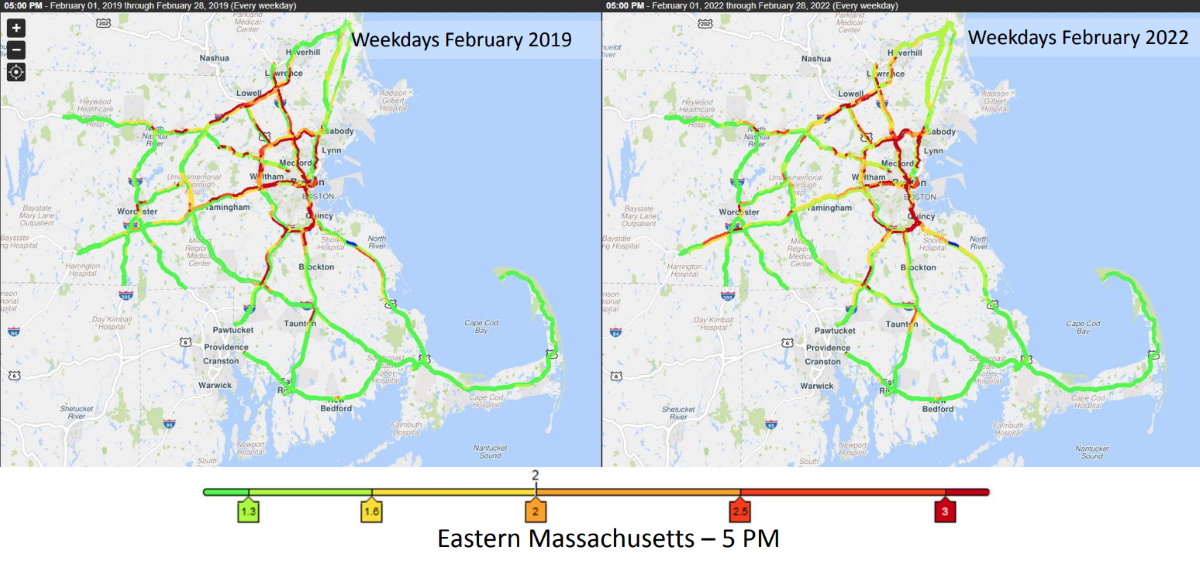

“A lot of that red is creeping back in,” Gulliver said, referencing traffic maps in his presentation. “Not quite as bad as where we were back in 2019 pre-pandemic, but getting closer by the week. I can tell you our traffic this morning, if you were driving anywhere, you would’ve seen that you had a lot of company on the roadway.”

The most headache-inducing changes for drivers appeared to land on I-93 between the Braintree split and the Massachusetts Avenue Connector.

In the evening, it now takes three minutes longer to traverse that stretch northbound on an average weekday than it did on an average weekday in 2019, a 20 percent increase, according to data Gulliver presented. But traveling between the same points in the same direction during the morning rush is more than three minutes faster today.

Driving that route southbound in the morning now takes nearly four more minutes than it did three years ago, reflecting a 30 percent increase in traffic, while the evening southbound change is a more muted half-minute increase.

The Massachusetts Turnpike has seen a widespread reduction in congestion, with morning and evening trips in both directions between I-95 and I-93 now running 9 to 24 percent faster than in 2019.

North Shore and Merrimack Valley drivers heading toward Boston on I-95 face an easier morning commute. Travel times between Route 3 and the Pike are six minutes shorter during the current a.m. rush than they were three years ago, and travel times northbound on I-95 from I-93 in Canton to the Pike are down 6.7 minutes from 2019.

“People are choosing to travel differently,” Gulliver said. “Yes, there’s still a lot of people that you’re going to see during those traditional peak times in the morning and the afternoon, those traditional commuting hours on pretty much every road are usually going to be the busiest of the day. But what we’re seeing here and what this demonstrates is that people are spreading out their trips, so even though the full volumes are getting close and sometimes exceeding (pre-pandemic), those peaks, although congested, are not as bad as they were in prior years.”

Underscoring the complexity, many of the changes in travel time have shifted from an analysis Gulliver offered over the summer.

For example, in July 2021, Gulliver said average evening rush hour travel on I-93 from the Zakim Bridge northward to I-95 was more than two minutes slower than in 2019. Today, p.m. traffic is moving along that same stretch nearly four minutes faster than in 2019.

Public transit use, meanwhile, remains significantly depleted from pre-pandemic rates despite steady growth in recent months.

Last month, MBTA General Manager Steve Poftak said ridership on the T’s core subway and trolley lines stood at about 45 percent of February 2019 levels. Buses, which peaked around 70 percent before falling during the winter, are back up to about 65 percent of pre-COVID ridership, he said.

The distribution of crowds has evolved on the T, too, just as rush hours might feel somewhat different on the state’s highways. More riders are taking trains and buses during the middle of the day, Poftak said, with an apparent but less pointed morning rush hour.

“There is a peak that has become a little bit more pronounced built around a 9-to-5 workday, but what I believe we are still seeing here is a lot of those 9-to-5 commuters we had pre-COVID are either not commuting, commuting intermittently, or they’re treating their days more flexibly,” Poftak said at a Feb. 24 MBTA board meeting. “We have a lot of people who used the system consistently throughout the pandemic who are not working a 9-to-5 day.”

Lingering alterations to commuting and to in-person work habits carry major implications for the future of downtown spaces and housing, in addition to spillover effects on restaurants and retail establishments that rely on weekday business from office workers.

Mass General Brigham Chief Human Resources Officer Rosemary Sheehan, who oversees HR for the state’s largest employer, said last month that the popularity of remote work “opened Pandora’s Box” in Massachusetts.

“We’re never going back,” she said. “We have to adapt to this new way of working and new way of living, quite frankly.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login