latest

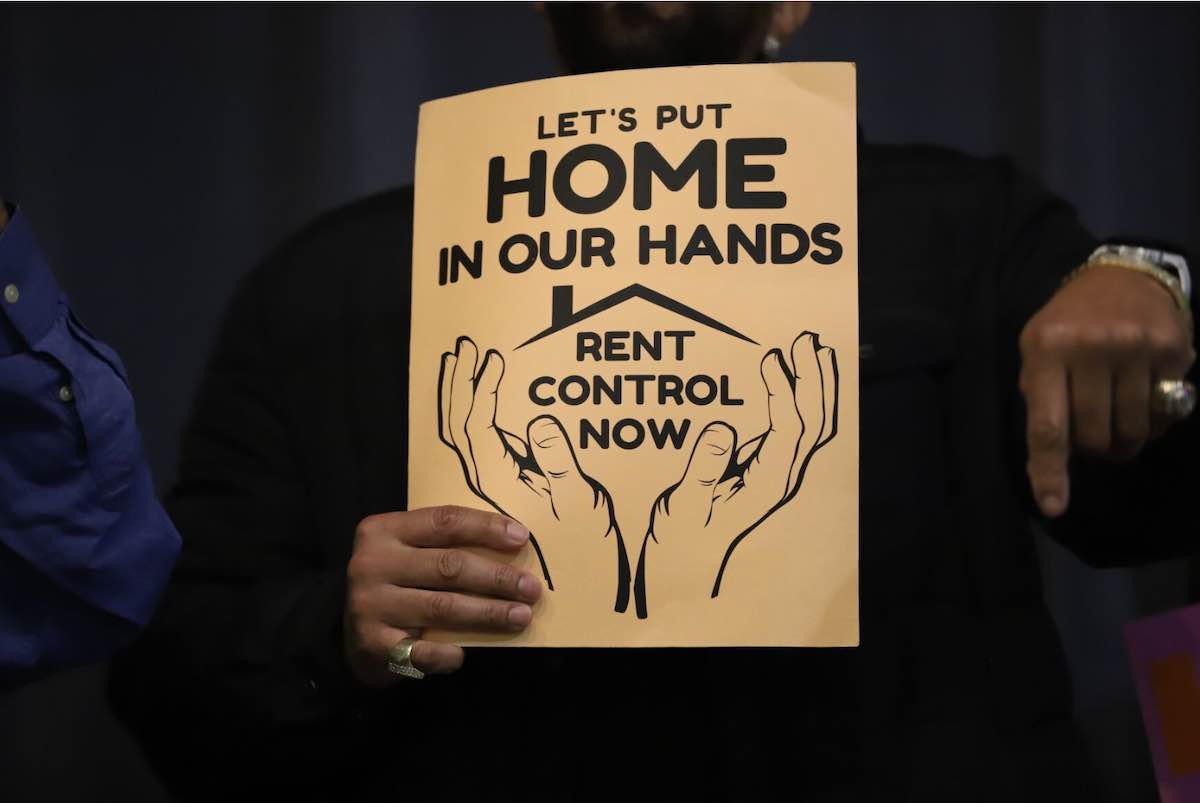

Massachusetts Rent Control Campaign Touted ‘Grassroots’ Signatures—But Relied on Paid Staff from Nonprofits

BY SAM DRYSDALE

After promoting its grassroots work and that it didn’t need to hire a paid signature gathering firm, campaign finance reports show that the organizers behind a proposed rent control ballot question relied on paid staff affiliated with supporting organizations to collect signatures.

Filings show the signature-gathering effort relied on paid staff at organizations backing the proposal, with those costs reported as in-kind contributions, raising questions about how “volunteer-led” and “grassroots” efforts are defined.

Of the 12 ballot questions that have so far qualified for the 2026 ballot, many hired professional firms that pay signature collectors directly, often on a per-signature basis. Supporters of the rent control proposal, organized under the Keep Massachusetts Home campaign, have said their effort was different and volunteer-based.

In a Dec. 2 press release, the pro-rent control committee Keep Massachusetts Home described its effort as “this year’s largest grassroots ballot signature gathering campaign — and the only successful signature gathering campaign not to hire a paid professional signature gathering firm.” The campaign reported collecting more than 124,000 signatures, well above the 74,574 required to stay in the mix for the 2026 ballot.

“Hundreds of volunteers collected signatures for the ballot initiative from voters in 332 of the state’s 351 cities and towns,” the campaign said, citing participation from labor unions, housing justice groups, and community and faith-based organizations.

Housing for Massachusetts, the committee opposing rent control, challenged that characterization after reports filed with the Office of Campaign and Political Finance (OCPF) showed almost $690,000 in in-kind contributions to Keep Massachusetts Home, much of it related to staff time, independent contractors and organizing expenses at nonprofit organizations.

Asked about the steep in-kind contributions, Andrew Farnitano, a spokesperson for pro-rent control Keep Massachusetts Home, said volunteers who collected signatures were not paid directly by the campaign, but through nonprofit organizations and community groups that support the question.

“Those are not volunteer signatures,” said Conor Yunits, chair of the committee opposing the ballot initiative.

Farnitano said the campaign has been careful in how it describes its signature-collecting effort.

“We’ve always been careful to say we didn’t hire a paid signature gathering firm,” Farnitano said. “There are certainly individuals who get paid by an organization who collected signatures while on payroll working for a nonprofit or another organization.”

More than 30 organizations filed in-kind contribution reports as part of the Keep Massachusetts Home ballot committee, Farnitano said. Some reflected minor expenses such as buying pizza or printing paperwork for volunteer events, while others involved staff members who either collected signatures themselves or coordinated volunteers as part of their regular work, he said.

Asked if any staff member or independent contractor who is paid by a supporting organization while collecting signatures should be considered a paid signature collector, regardless of whether the ballot committee itself paid them directly, Yunits said “yes.”

“To their credit, their OCPF report is very accurate and they disclosed appropriately. But it’s misleading for them to say they gathered signatures without paying for them. They were just paying for them in a different way,” Yunits said.

The in-kind contributions covered expenses ranging from staff time, independent contractors, transportation, food, supplies, and in some cases travel and lodging.

Campaign finance records also show about $75,490 in in-kind contributions for travel expenses tied to the signature-gathering effort. The largest portion of that total — $67,729 — was reported by Springfield No One Leaves through its out-of-state fiscal sponsor for “travel and lodging.”

“People traveled mostly to and from Boston and Springfield for events,” Farnitano said. He added that each organization reporting in-kind contributions is responsible for maintaining its own records. “They might say, during this period of all of 2025, we spent $300 on train tickets for our staff who were traveling around collecting signatures. We try to encourage groups to overestimate instead of underestimate. If there’s any questions we err on the side of more transparency.”

Farnitano contrasted that approach with campaigns that pay large sums directly to professional signature gathering firms.

“It’s a lot simpler when you can write a simple check, some of the campaigns this year — $1 million or more — to paid signature gathering,” he said.

There’s a range in the expense for campaigns that use these professional gathering firms. The ballot question to reform zoning for single-family homes with the goal of building more housing spent about $1.3 million on professional paid signature circulating; the question to allow election-day voter registration spent $75,000; and the measure to overhaul the Legislature’s stipend system spent $300,000. Other campaigns also hired professional collectors.

The distinction of hiring a firm is important, Farnitano said.

“I think that paints a very different picture of what it means to get on the ballot. We didn’t do this by cutting a big check, we did this through dozens of organizations that have a permanent presence in Massachusetts,” he said.

The News Service asked Yunits if he thought there was a distinction between hiring a paid signature collecting firm and relying on nonprofit staff who collect signatures as part of broader organizing work.

“I see a meaningful distinction between campaigns that claim they were gathering signatures through all volunteer efforts when in reality they were paying for signatures,” he said. “In my mind it reinforces that they were relying on emotion rather than fact, much like their arguments for their ballot question are not based on data or fact.”

Farnitano said the difference lies in who was paid and how.

“These are dozens of grassroots organizations made up of thousands of members and volunteers,” Farnitano said. “They also have a number of paid organizers and staff members who work for those nonprofits, and collected signatures during the workday and properly documented that during the workday.”

He argued signature gatherers hired through a firm sometimes do not understand the policy they are collecting signatures for, and there’s a personal incentive, as they often get paid-per-signature.

“These are collected by people who actually support rent control, they care about the housing crisis facing Massachusetts,” he said.

Some of the largest in-kind contributions cited by opponents involved local housing and tenant organizations that are fiscally sponsored by national nonprofits. For example, Springfield No One Leaves reported more than $137,000 in in-kind contributions through its fiscal sponsor, the Brooklyn-based Right to the City Alliance, covering staff time, independent contractors and travel and lodging.

Farnitano said fiscal sponsorship arrangements allow smaller organizations without their own IRS-designated nonprofit status to operate under the umbrella of larger nonprofits.

“They don’t have their own 501(c)(3) established with the IRS but are under the umbrella of the larger nonprofit entity,” he said. “They are legally a sub-entity of that larger nonprofit… but the work has been done by those smaller community groups.”

Similar arrangements exist for Lynn United for Change through Tides Advocacy, based in Santa Monica, California, and for United for a Better East Boston and Reclaim Roxbury through Resist Inc., Farnitano said.

“It’s clear a number of these national groups have an agenda that is not related to these affordability problems here in Massachusetts,” Yunits said. “The reality is that the best way to address the affordability crisis is creating more housing.”

In their end-of-the year report, the anti-rent control committee reported six donations and one in-kind contribution. The donations ranged from $20,000 to $200,000 from real estate interests, totaling $431,600. They also received an in-kind contribution from Masslandlords, Inc. based in Cambridge for “grassroots engagement” worth $26,634.