latest

Massachusetts employers face “staggering” hike in unemployment taxes

By Chris Lisinski

With unemployment soaring, state lawmakers are considering ways to soften the blow from a major impending increase in the taxes employers pay toward the state’s unemployment system, a jump in costs that one business group described as a “pretty staggering.”

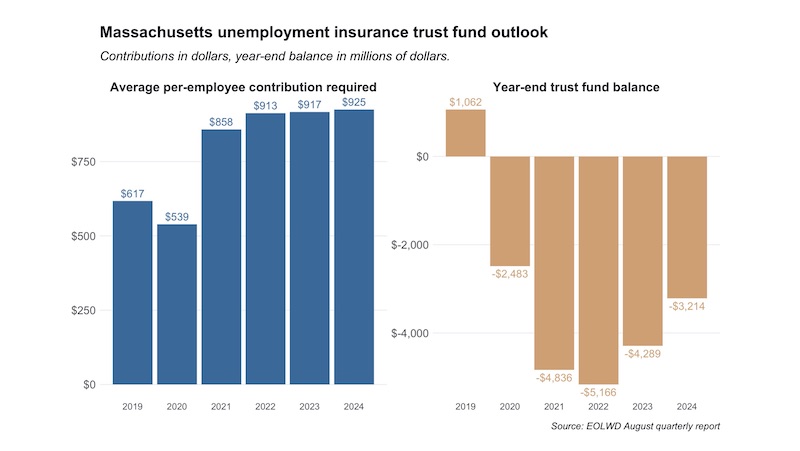

Massachusetts officials project that the unemployment insurance trust fund deficit will grow to more than $2.4 billion by the end of the year, prompting a nearly 60 percent increase in the contributions that employers pay to keep benefits flowing to the jobless. [Chris Lisinski/SHNS]

With the unemployment insurance trust fund suddenly facing a multibillion-dollar deficit over the next four years, the contributions required from Massachusetts businesses are set to increase nearly 60 percent when the calendar turns to 2021 and then continue growing at a smaller rate through 2024.

Those higher taxes — estimated at an average of $319 more per qualifying employee next year — will be due starting in April, raising concerns that the sharp uptick will put a drag on the economic recovery from the ongoing COVID-prompted recession and make it more difficult for employers to bring back jobs they cut.

Christopher Carlozzi, state director for the National Federation of Independent Business Massachusetts, said his group and the employers with which it works view the projected increases as “a looming crisis.”

“It’s almost a Catch-22,” Carlozzi said in an interview. “You want these businesses creating jobs. Now you’re making it prohibitively more expensive to create a new job by increasing the tax on employers simply to employ people.”

The Legislature has on occasion stepped in to prevent a significant increase from hitting employers, but it’s unclear if it will do so this year. Lawmakers continue to weigh ideas to accelerate economic growth.

During the Great Recession, lawmakers and former Gov. Deval Patrick agreed to several consecutive years of unemployment insurance rate freezes amid projections that the rate schedule would climb to the highest allowable level.

A key lawmaker said this week that the anticipated increase in 2021 might not come to pass.

Sen. Patricia Jehlen, who co-chairs the Labor and Workforce Development Committee, told the News Service she believes the Legislature will look to freeze rates on employers to limit the additional strain, but stressed that because of the size of the shortfall, the federal government will need to play a role in any solution.

“Traditionally, and I think we would want to do this again, we would need to freeze,” Jehlen said. “We would love to freeze rather than allowing it to go up during a recovery because so many businesses are in trouble. But we really need help from the feds to make that possible.”

“Like everything else, we’re just totally dependent on the federal government in this situation,” she added.

Over the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Massachusetts — like many other states — faced an unprecedented level of demand for joblessness benefits and demand remains high. The state paid more than $4 billion in aid between January and July, compared to just $812 million over the same period in 2019.

The account used to pay those claims was not equipped for the sudden surge. At the end of July, it was already $748 million in the red, and the Baker administration projected in an August quarterly report that the shortfall will grow to nearly $2.5 billion by the end of the year.

Each of the following four years will also run negative, officials estimate, pushing the five-year total to a roughly $20 billion net deficit — an outlook that is somewhat better than the $27 billion net deficit projected in the previous quarterly update issued in May.

To help prevent the fund from becoming insolvent, the average cost per employee is estimated to increase from $539 in 2020 at rate schedule E to $858 in 2021 at rate schedule G. Officials expect to remain at the highest rate schedule through 2024, topping out at an average cost per employee of $925 in the final year of projections.

Carolyn Ryan, senior vice president of policy and research for the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, said her group’s members are also worried about the impact of the higher contributions amid a recession.

She and other business leaders are weighing possible advocacy efforts, but Ryan warned that the unemployment taxes are “probably the first of many bills” from the pandemic — an economic crisis she said will likely surpass the Great Recession — that Massachusetts will need to pay.

Lawmakers have yet to even embark on debate over an annual budget with a four-month interim spending plan currently in place, and while tax collections are holding up early in fiscal 2021 experts previously said the state could fall billions of dollars short of pre-pandemic tax revenue estimates.

“There’s going to have to be shared pain. It’s probably some budget cuts, probably some borrowing, probably some revenue raisers in the mix of those,” Ryan said. “It’s going to be painful no matter what. That’s the really sobering part of this. It’s stuff that, if I were in charge, would keep me up at night.”

The current outlook has revived broader debate about the state’s unemployment system and whether its eligibility and benefit levels need to be reformed.

Carlozzi, whose group has been pushing for changes to UI infrastructure for years, said the forthcoming strain makes a clear case that Beacon Hill should consider raising the bar for benefits and lowering the requirements on employers.

He pointed to a December 2019 report from The Tax Foundation, a think tank that broadly supports lower tax burdens, that placed Massachusetts dead last among states in a nationwide ranking based on its rates and its $15,000 taxable wage base.

“It is something lawmakers may want to consider at this point because it’s going to be a difficult tax to pay for employers, especially those looking to get people back working again under very difficult circumstances,” Carlozzi said. “They really haven’t had an appetite to do it, but it might be the time.”

Labor organizations have often resisted calls to restructure the system, describing unemployment benefits as a key crutch to keep workers afloat during challenging times and promote economic development.

Phineas Baxandall, a senior analyst at the left-leaning Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, argued that agreeing to scale back the system would only set the state up to fall short at protecting its residents from future economic harm.

“To me, one of the real lessons from the last months is how the unemployment system has saved the Massachusetts economy from freefall,” Baxandall said. “It has saved us from a chain reaction in which layoffs erase consumer demand and even workers with jobs cease spending because they’re just a pink slip away from destitution.”

A key factor in the current situation, he said, is that the trust fund did not build up stronger reserves during years of growth following the most recent recession — something he tied directly to advocacy by business-friendly groups.

Massachusetts for years has fallen short of a ratio between benefit costs and wages, referred to as the average high cost multiple, phased in by federal regulations.

“We’re coming off of the longest-ever recorded economic expansion, and yet our reserves were not particularly strong,” Baxandall said. “That’s not because the system that was created was flawed. It was because the system that was created was not allowed to work. Time after time, these same kinds of business organizations suspended the smaller increases in the payroll tax that were meant to keep our unemployment trust fund well-funded.”

States with stronger performance qualify for interest-free advances from the federal government. In 2019, Massachusetts needed a trust fund balance of $3.93 billion to meet that threshold, but the account totaled only $1 billion at the end of the year.

That carries further cost implications during the COVID recession: according to U.S. Treasury data, Massachusetts has already received nearly $1.3 billion in loans from the federal government to cover the trust fund as of Friday, which will eventually incur interest. The current interest is 2.4 percent, according to the Treasury.

The state Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development anticipates interest payments on any unpaid federal advances would be due starting in September 2021.

“The Department of Unemployment Assistance continues to monitor the latest trust fund projections and will continue to work with state and federal partners to ensure that financial benefits are delivered and funded during these unprecedented circumstances,” EOLWD spokesperson Charles Pearce said in a brief statement.

As lawmakers look toward the federal government for help, Ryan cautioned against overreliance on dollars that Massachusetts will need to pay back.

“While it’s helpful to have (the federal government) fill in and the magnitude of some of these expenses can only be filled by the federal government, it’s not free money,” she said.

With more than 1.7 million claims for standard or expanded unemployment insurance since the start of the pandemic, Massachusetts residents have leaned heavily on the system. The state has topped national rankings in unemployment rate for each of the past two months, at 17.7 percent in June and 16.1 percent in July.

The higher assessments are also scheduled to kick in at the same time that workers gain access to paid family and medical leave under a 2018 law. Payroll taxes of 0.75 percent to fund those forthcoming benefits started on Oct. 1.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login